Surface Phonons in III-V Semiconductors computational approach

Z.Azdad Möri

The author independently carried out all calculations, measurements, and data interpretations presented in this work

Surface phonons arise due to the disruption of translational symmetry at the surface of a solid, leading to

vibrational

modes that are confined near the surface. These excitations exhibit extraordinary properties that

distinguish

them from

bulk phonons. Of particular interest is their strong coupling with electromagnetic waves, which has enabled

a

range of

advanced applications in nanotechnology and thermal management. For example, surface phonon polaritons can

be

harnessed

as sources of coherent and monochromatic thermal radiation. Furthermore, their ability to mediate near-field

radiative

heat transfer enhances thermal energy exchange at the nanoscale, making them promising candidates for

improving

the

performance of thermophotonic devices, nanoscale heat engines, and thermal imaging systems.

Although the existence of surface phonons has been extensively studied using neutron scattering techniques,

measuring

their characteristics at the nanoscale remains a challenging task. Techniques such as Electron Energy Loss

Spectroscopy

(EELS) have been employed to study them; however, the spectral resolution of such techniques is often

insufficient to

provide deep insights. In contrast, Raman spectroscopy is considered one of the most effective tools for

probing

surface

modes, particularly at the Γ-point.

This study investigates surface phonon polaritons (SPhPs) in gallium phosphide (GaP) nanowires, focusing on

their

emergence, characterization, and dependence on environmental and experimental conditions. Using a

combination of

first-principles density functional theory (DFT), Boundary Element Method (BEM) simulations, and

polarization-resolved

Raman spectroscopy, the work provides a multi-faceted approach to identifying and analyzing SPhP modes.

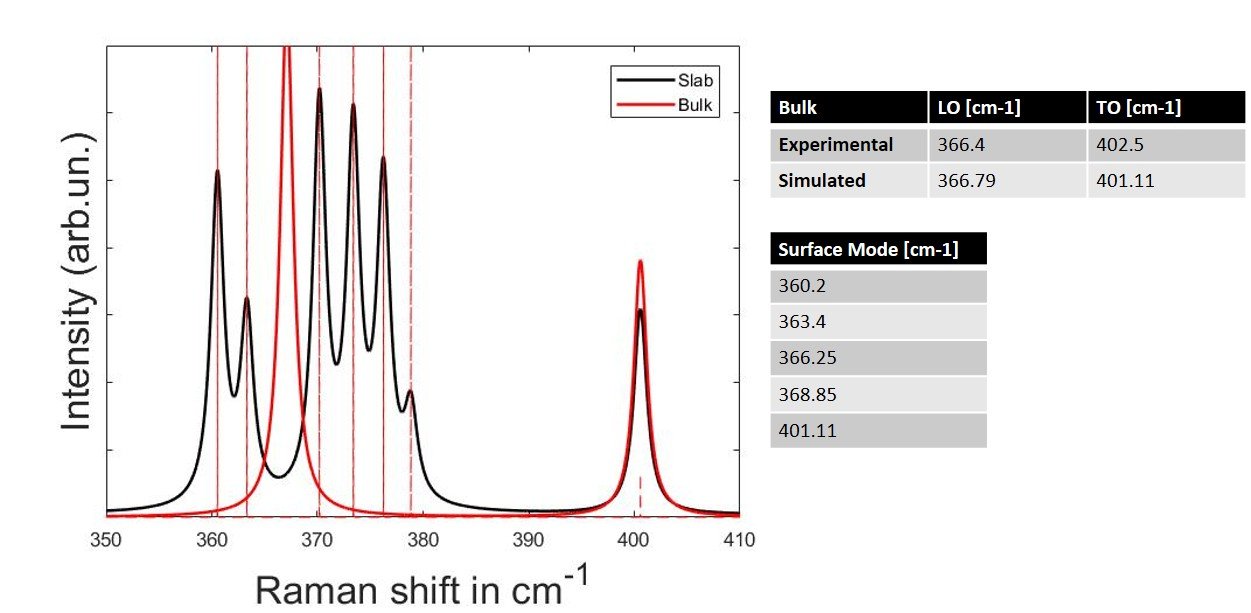

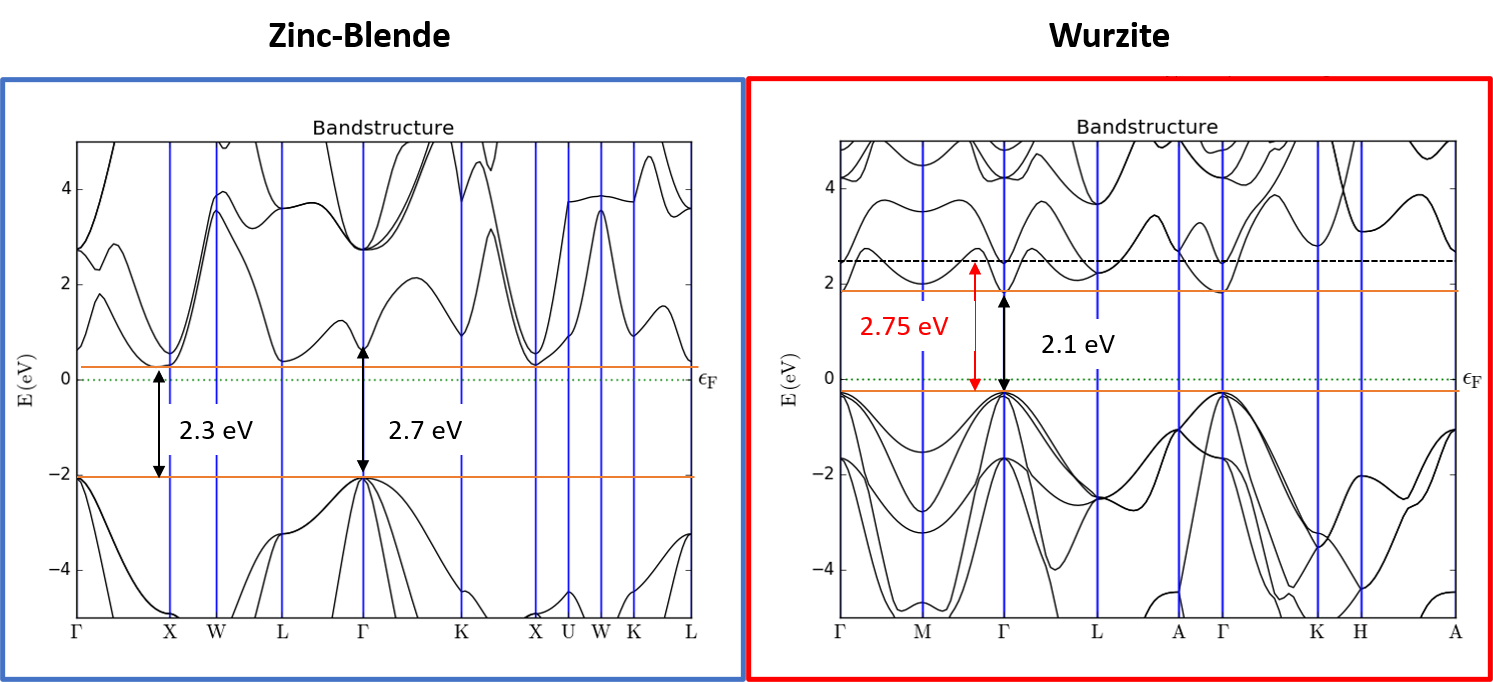

Simulations of zinc-blende GaP slabs revealed Raman-active surface modes within the Reststrahlen band, known

to strongly

interact with electromagnetic radiation. Since DFT simulations of realistic wurtzite nanowires are

computationally

demanding, Raman spectra were used to extract dielectric functions for BEM modeling.

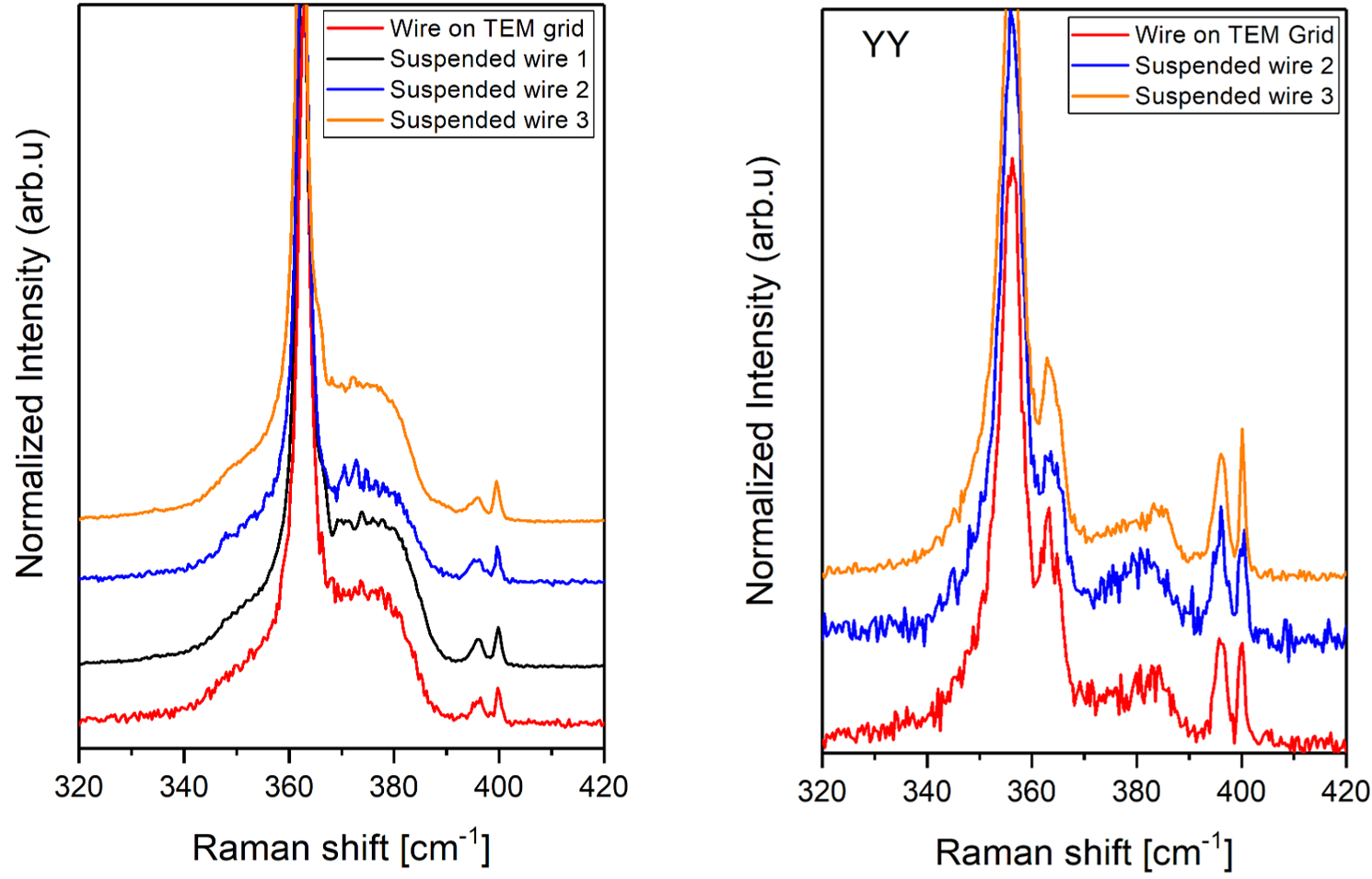

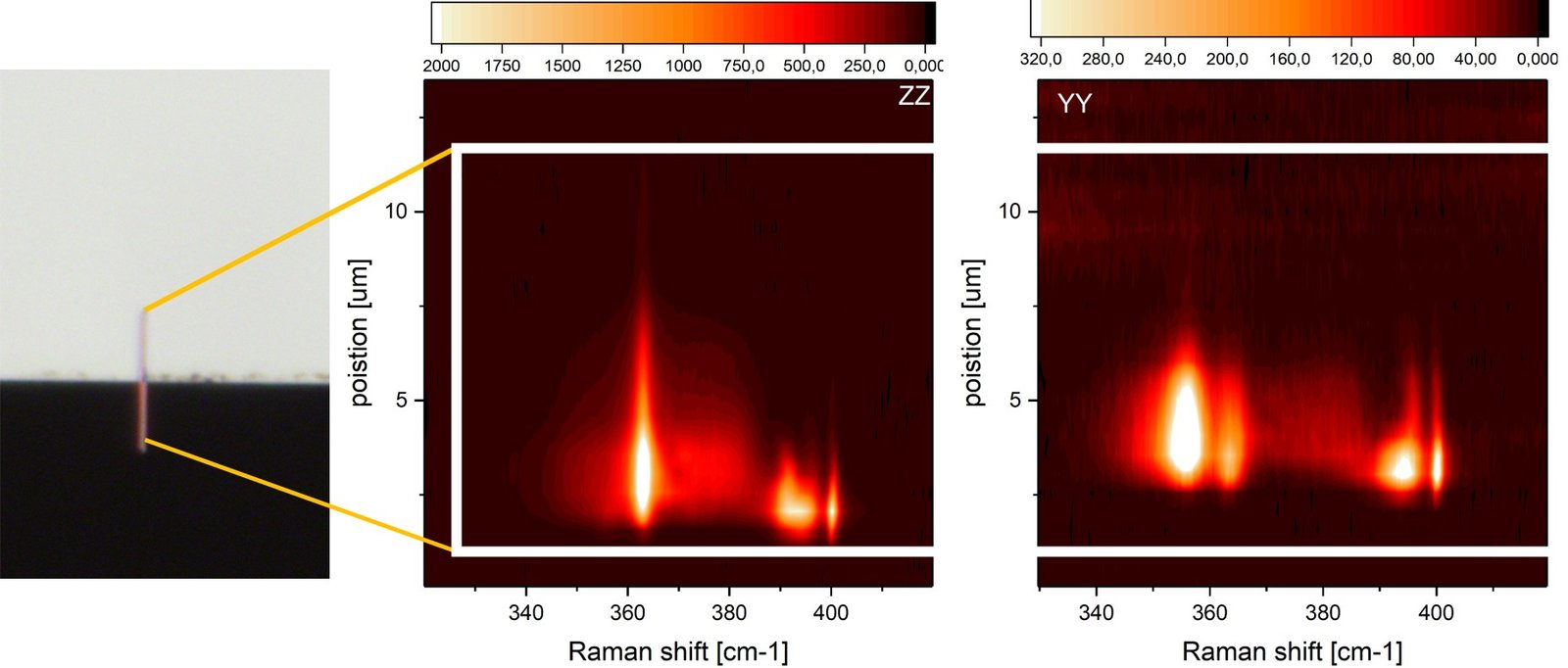

Experimentally, Raman spectroscopy was performed on GaP nanowires placed in various configurations: on

substrates,

suspended on TEM grids, and cantilevered above silicon. Clear surface phonon signatures were observed only

in suspended

geometries, where dielectric symmetry was preserved, confirming the environmental sensitivity of SPhPs. A

significant

angular dependence of these modes was demonstrated, with polariton and Fröhlich-Klemens (F-K) modes merging

at higher

incident angles, notably at 45°, signaling strong resonance effects.

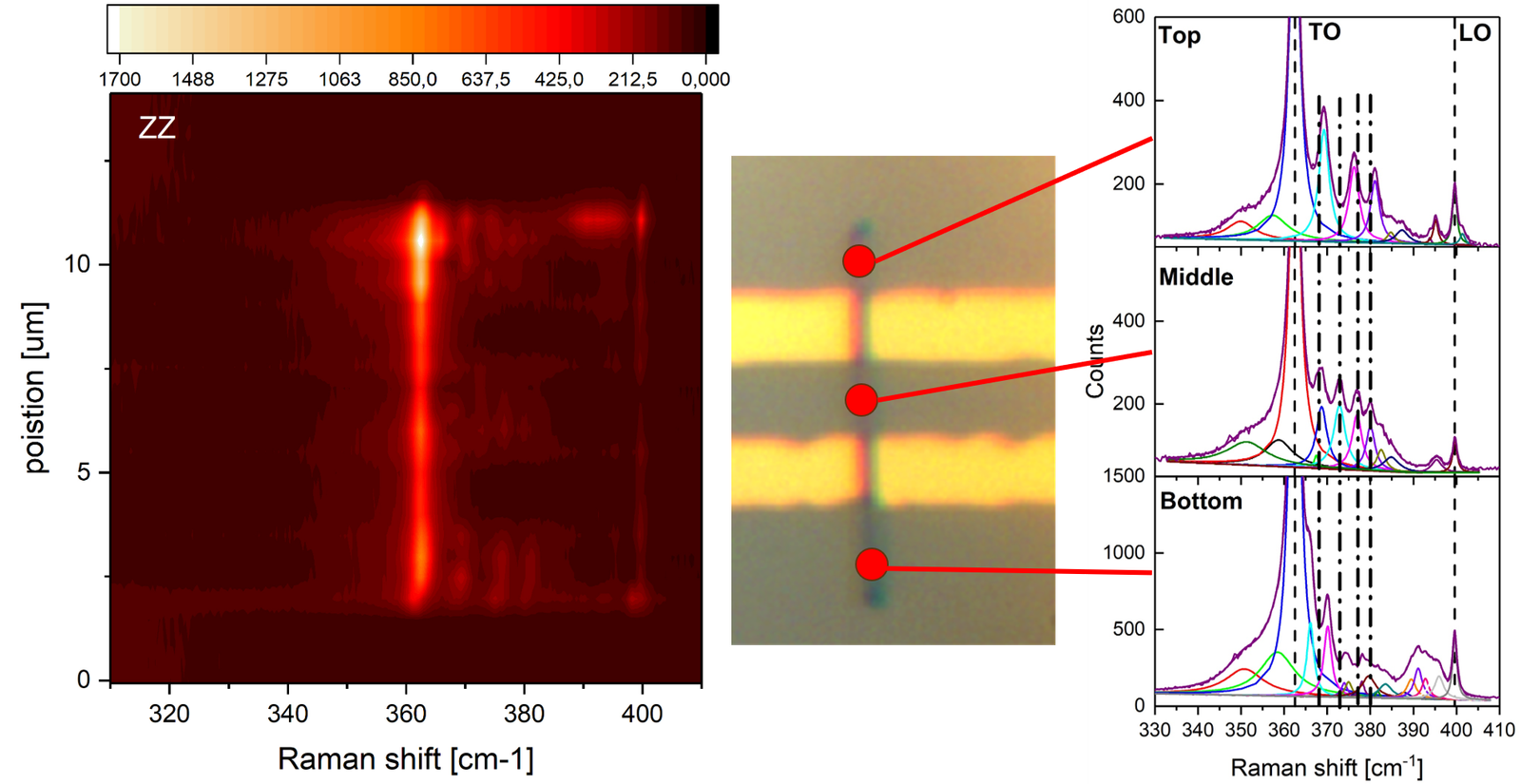

Further, by placing nanowires over periodic gold strips, the study demonstrated spatial modulation of the

SPhP

intensity—absent on gold and pronounced in suspended regions. This was corroborated by BEM simulations,

aligning with

observed periodic spectral changes along the nanowire.

DFT Calculation of Zinc Blend Surfac phonons along the 111 Direction

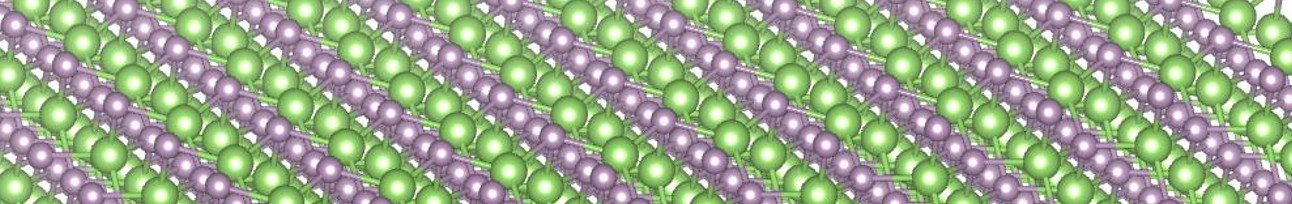

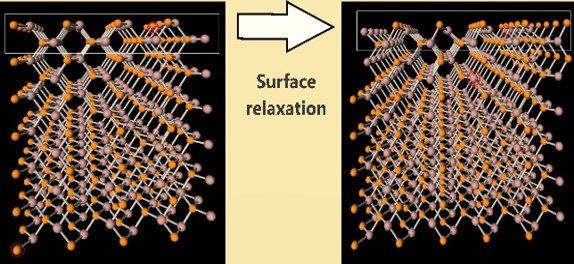

Building a crystal structure for simulating a slab is often done by constructing a unit cell that is periodic along two directions (X and Y) and introducing a sufficient vacuum gap along the Z direction to prevent interactions between periodic images of the slab.Although this approach becomes computationally challenging as the unit cell size increases, it remains the most reliable method for addressing surface-related phenomena. This technique is widely used to study the surface electronic structure of materials and chemical reactions occurring at material surfaces. Simulations of full phonon dispersion have been extensively performed for various classes of materials, with results often compared to experimental data from neutron scattering techniques.

However, to the best of my knowledge, Raman spectra of a surface phonon slab of GaP have not yet been reported.

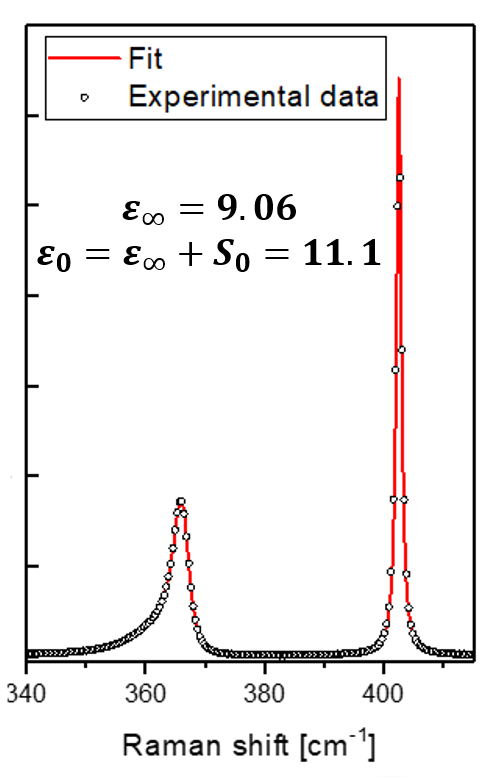

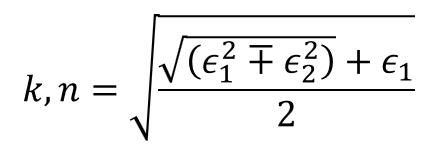

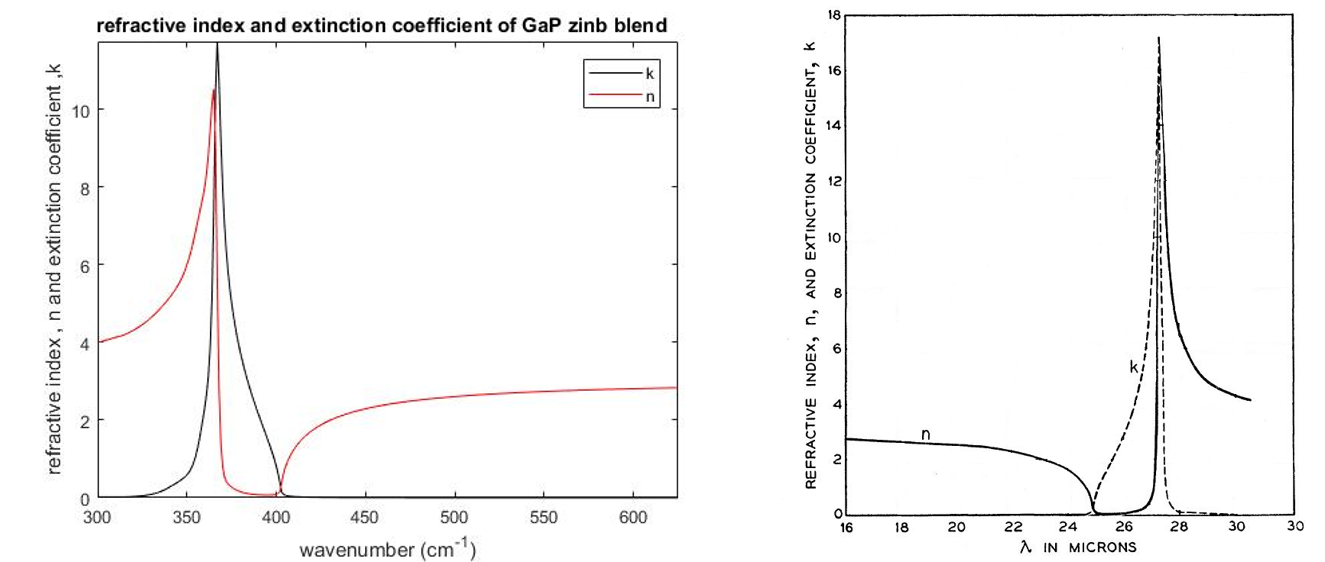

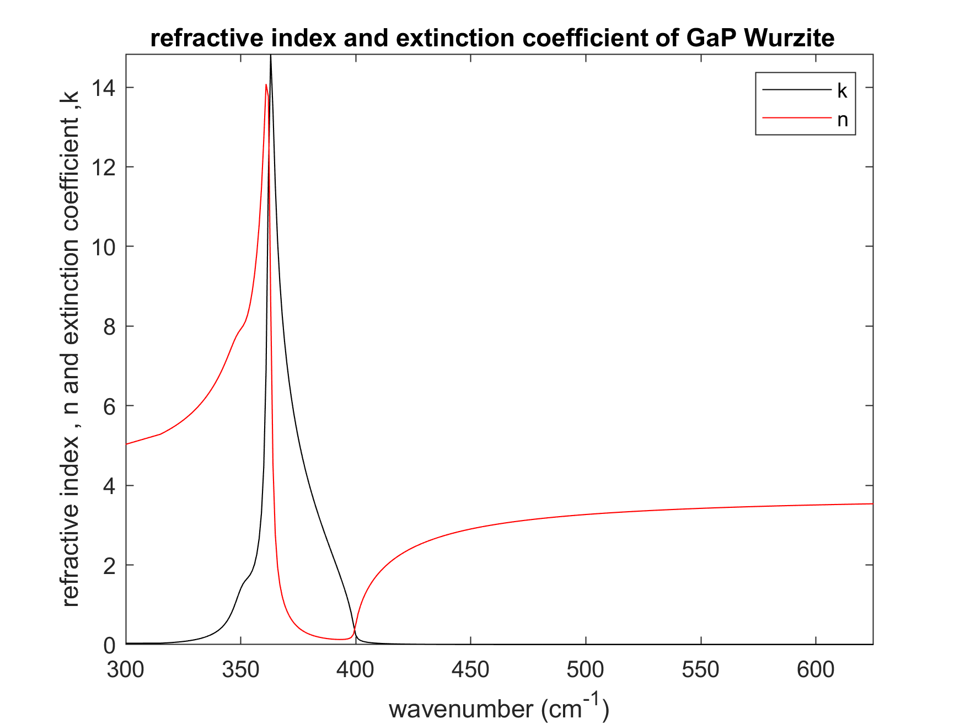

Fortunately, there exists a method to reconstruct n and k from Raman spectra. This is achieved by fitting the Raman response as described by A. S. BARKER.

$$ \varepsilon = \varepsilon_\infty + \frac{S_0\left(1 - \sum_{i=1}^{n} S_i \right)\nu_0^2} {\nu_0^2 - \nu^2 + i\nu\gamma_0 - \sum_{i=1}^{n} \frac{S_i \nu^2 \nu_0^2}{\nu_i^2 - \nu^2 + i\nu\gamma_i}} $$ The results of the fit are shown in the following graph:

Now that we have a robust model we can reconstruct the dispersion relation n and k using the following formula:

Where:

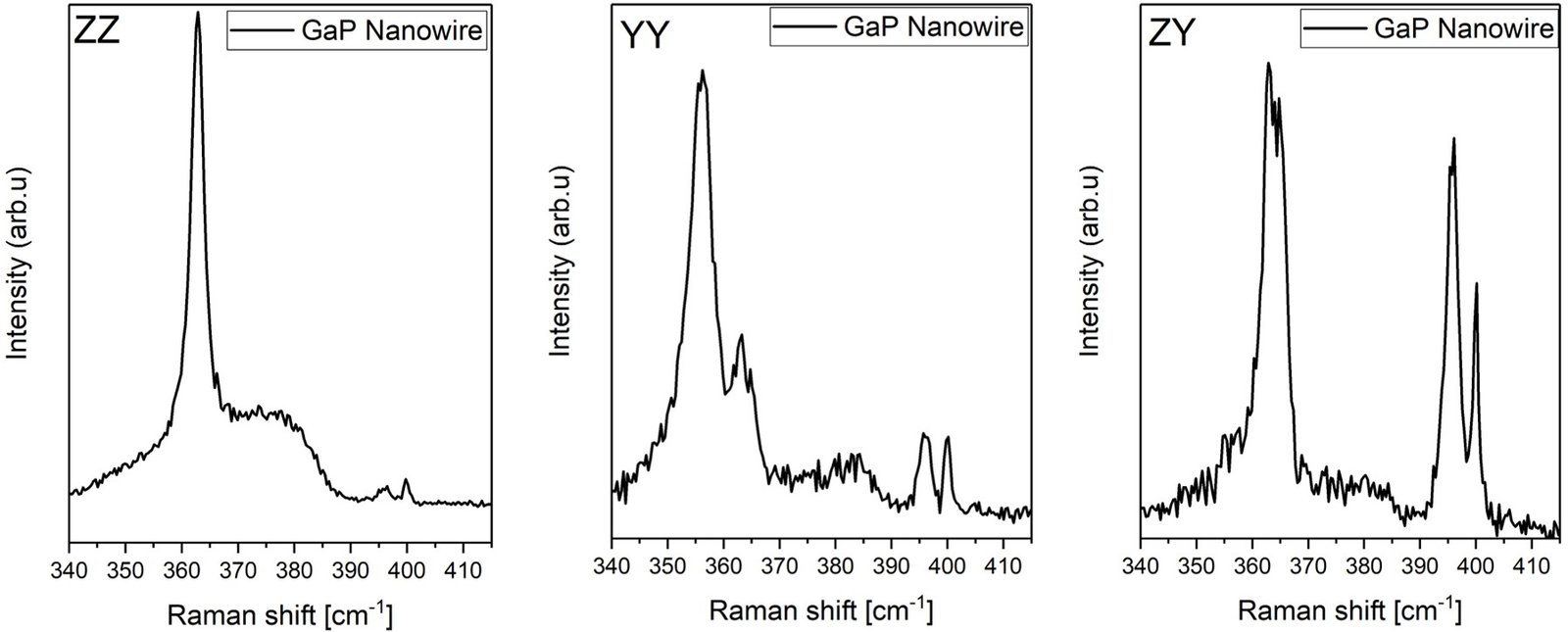

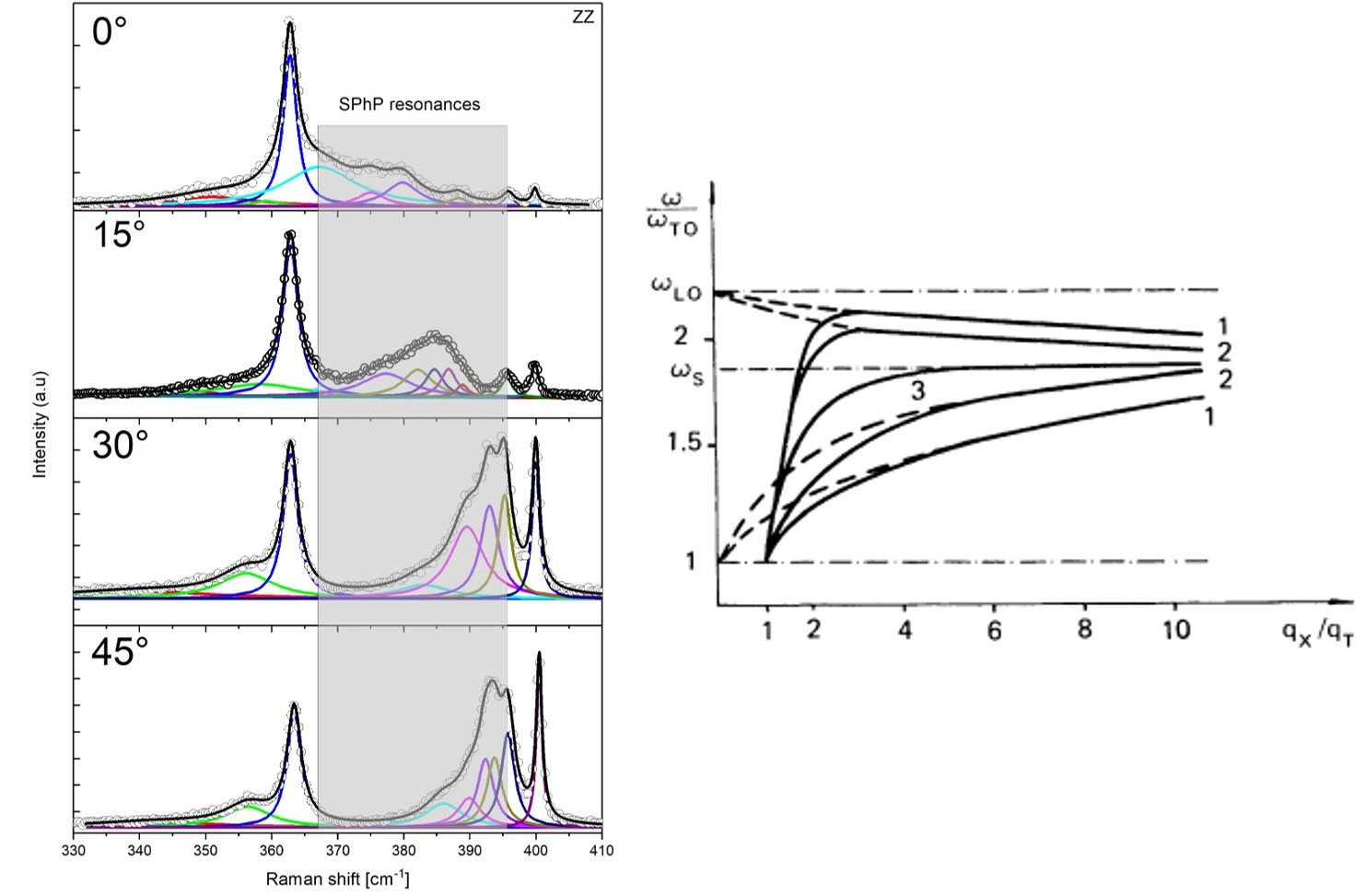

In the following section, we present a significant breakthrough in the identification and analysis of surface phonon modes in wurtzite GaP nanowires. The distinct signatures of individual surface modes are revealed, and their corresponding frequencies are calculated using boundary element method (BEM) simulations. To unambiguously demonstrate the existence of these modes, Raman spectra were acquired from a single nanowire transferred onto a TEM grid, ensuring a suspended configuration ideal for supporting surface phonon polaritons. The same nanowire was subsequently imaged via transmission electron microscopy to confirm its wurtzite crystal structure, thereby eliminating variability arising from structural differences among grown nanowires. The recorded Raman spectra, obtained under the three principal polarization configurations, are presented below.

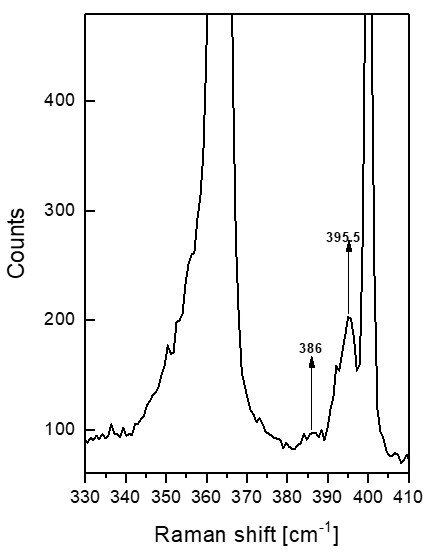

In the cross-polarized configuration—where the incident electromagnetic field is oriented perpendicular to the nanowire growth axis pronounced Fröhlich-Klemens (F-K) mode emerges at 396 cm⁻¹. Unlike conventional Raman-active modes, the F-K mode arises from a combination of non-zone-center phonons, specifically involving longitudinal optical (LO), TO, and acoustic phonons. Because it does not conform to standard Raman selection rules, the F-K mode is observable across all polarization configurations.

A lower-energy F-K mode, centered at 386 cm⁻¹, is particularly well-resolved under YY and ZY polarizations.

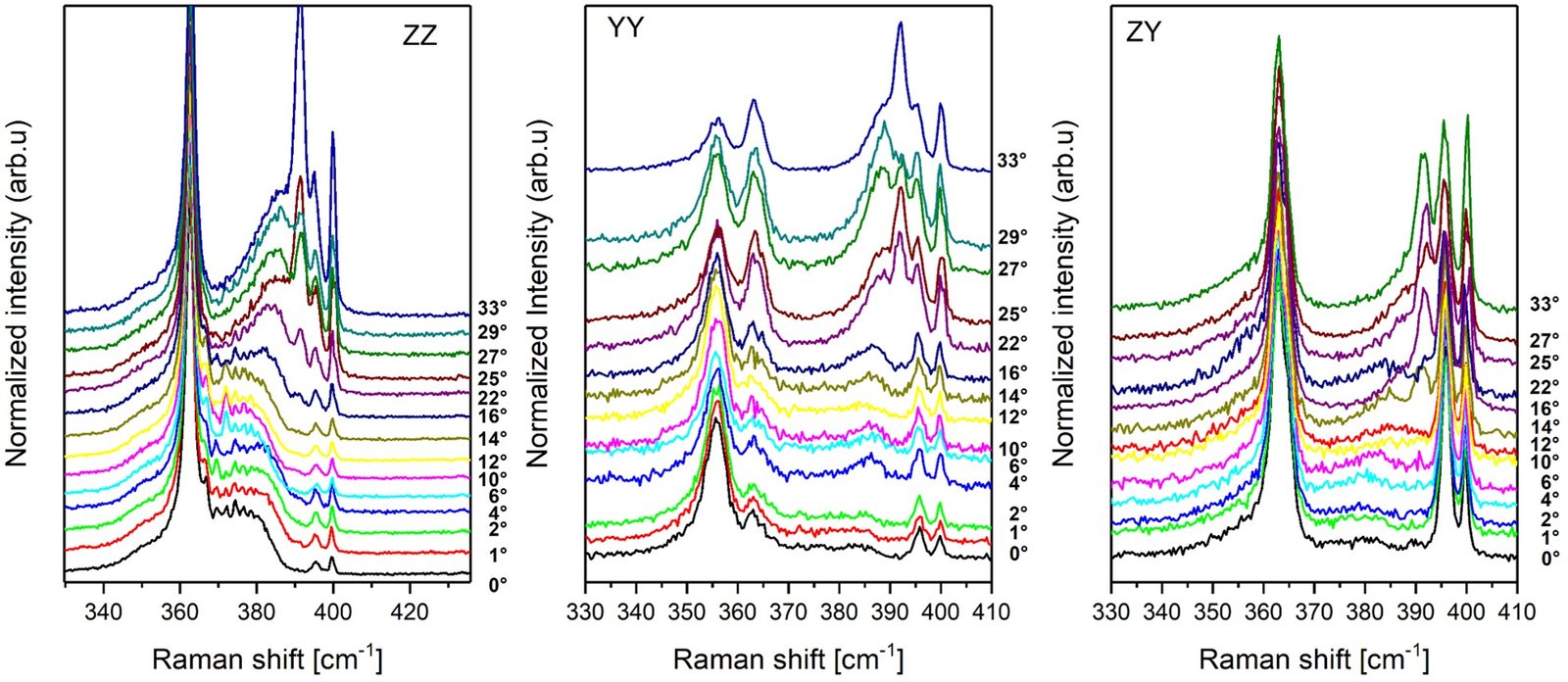

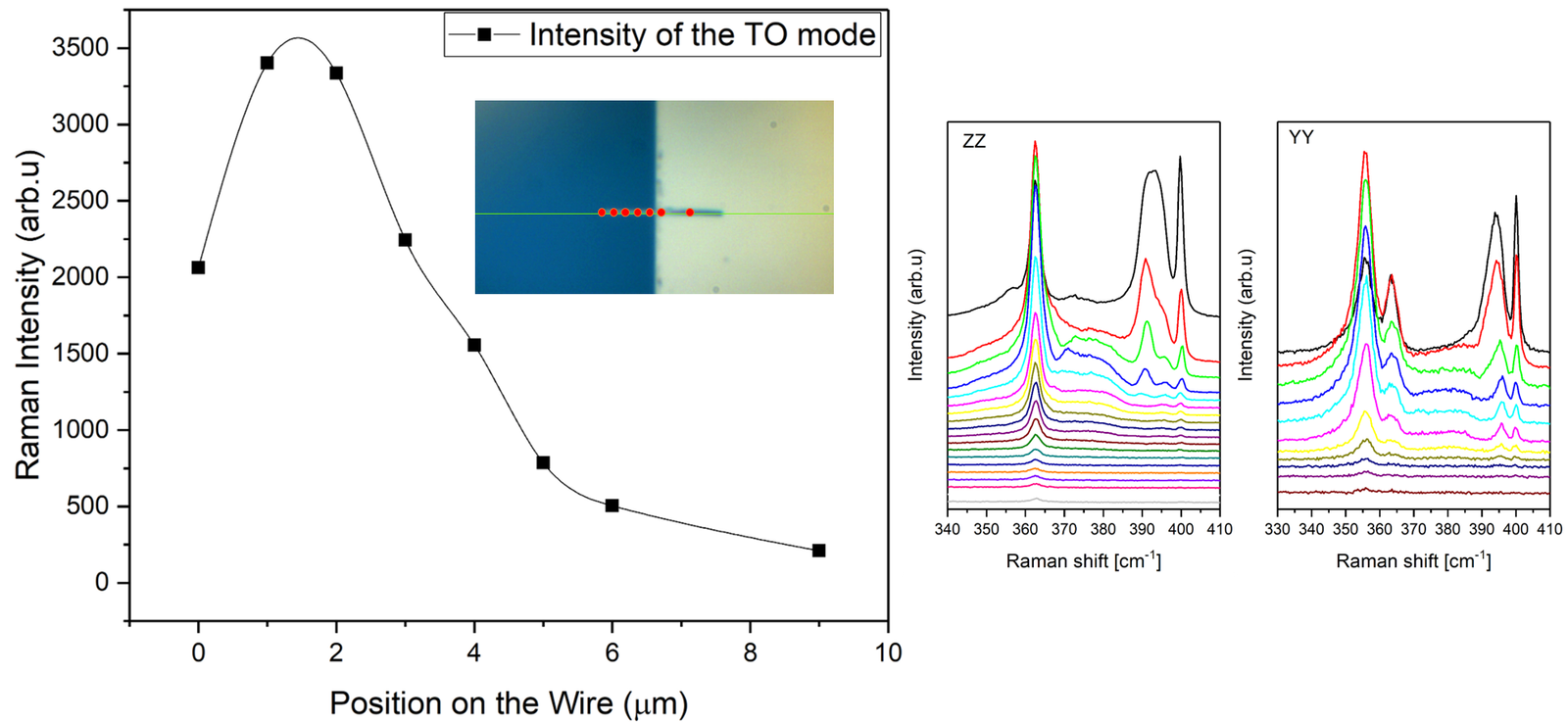

Upon varying the angle between the incident light and the nanowire growth axis, a systematic shift in the polariton mode position is observed. This angular dependence modulates the resonance conditions, leading to the progressive suppression of surface phonon features in the Raman spectrum. Notably, as the polaritons mode approaches its convergence limit, the intensity of the LO phonon mode increases, and a resonant peak emerges—exceeding the intensity of both the LO and TO modes.

Theoretically, as the convergence limit is approached, the two modes are expected to merge into a single polaritonic mode. However, this limit cannot be reached under the experimental conditions presented here. Nevertheless, at a higher incidence angle of 45°, the F-K phonon and the polariton features in the spectrum begin to merge, forming a broader, more unified peak.

As the excitation spot approaches the substrate interface, a significant decrease (16-fold) in the overall Raman signal is observed, accompanied by the gradual disappearance of the surface phonon modes. This attenuation can be attributed to reduced light–matter interaction at the substrate boundary, increased optical losses, and possible disruption of surface-specific vibrational coupling. This was observed on all the measured Nanowires under the cantilivered configurations.

Let us know explore an other scenaria where a pure GaP wurzite Nanowire is placed on parallel strips of gold. The reason behind this experiment is to investigate the role of alternating symmetric and asymetrical medium. As shown above the SPhP should get surpressed when the Nanowire is in contact with a substate.

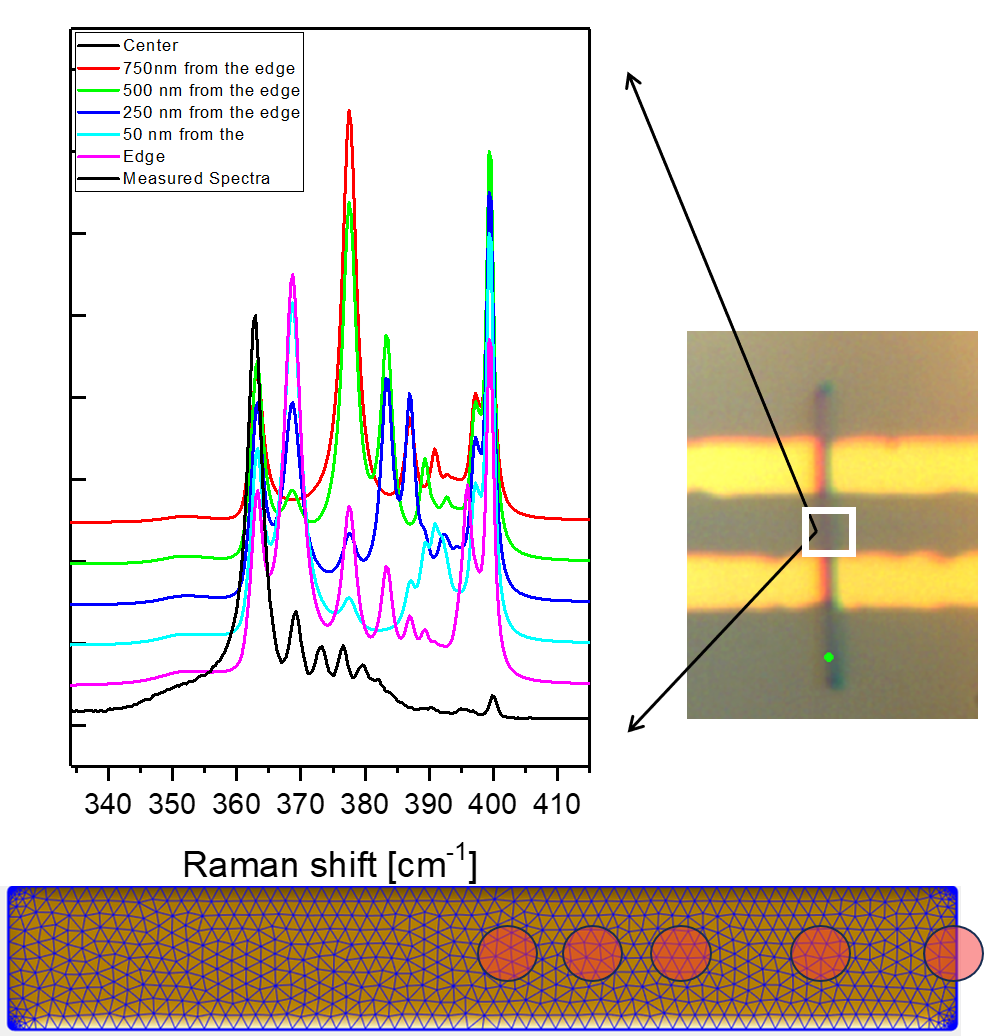

To better understand this behavior, a boundary element method (BEM) simulation was performed using the SPhP Toolbox on a GaP nano-rectangle. The simulation employed the refractive index values (n and k) characteristic of the wurtzite phase, which were extracted from fitting the experimental Raman spectra. The simulated structure had dimensions of 100 × 150 × 2000 nm. Spectra were calculated at several lateral positions: at the edge, and at 250 nm, 500 nm, 750 nm, and at the center of the nano-rectangle. Given the laser spot size (~920 nm), it is reasonable to assume that the measured Raman signal represents a spatial average, incorporating contributions from all these positions.

The results are shown below:

Conclusion

This work presents the first comprehensive angular mapping of surface phonon polaritons in GaP nanowires, supported by both theoretical modeling and experimental validation. It conclusively demonstrates that SPhPs are highly sensitive to dielectric environments, polarization, and incident angle, and can be selectively excited in suspended geometries. The findings highlight the potential of SPhPs for next-generation applications in coherent thermal radiation control, nanoscale heat dissipation, and quantum sensing, where controlled phonon–photon coupling is critical. These insights pave the way for engineering phononic and photonic devices that exploit surface vibrational modes at the nanoscale. ← Back to Portfolio